Halberstam recalls the wretched early days after Sept. The whole company is missing?' " asked one retired veteran when he called for a report on his son's whereabouts. " `What the hell does that mean, Thirty-five Truck is missing?. Halberstam writes about the sheer incomprehensibility of what was unfolding that day, even to the many fathers who had welcomed their sons into the business.

11, when wives and parents called in a frantic hunt for information. Woven among the snapshots is a re-creation of the morning of Sept. Frank Callahan, known for his withering form of non-verbal feedback, "The Look" Steve Mercado, the proud young Puerto Rican who "was constantly campaigning for stickball to become an official Olympic sport" so his sons, ages 6 and 2, could compete someday.

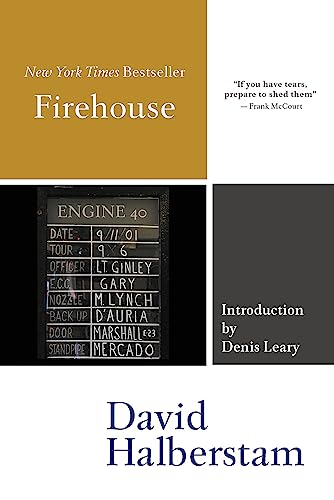

Indeed, above all, this book is a series of vivid and tender portraits: Bruce Gary, the hulking house leader with boots so big they arrived in two boxes and an edge that made him a bit like "a human cactus" the strapping Jimmy Giberson, who greeted neighbors at the firehouse door, where he liked to take his morning coffee the distant but revered Capt. Halberstam writes about what makes a good firefighter ("Calm is the most basic of the positive words that firemen use to describe each other") and the qualities that distinguished some who died. 35, which sent a combined 13 men to the burning World Trade Center and received only one back alive. The result is "Firehouse," the intimate portrait of Engine Co. As a New Yorker, however, Halberstam sought to record the story of his city's darkest day from a narrower view that made perfect sense: his own neighborhood firehouse. As a journalist, he specializes in sweeping takes on war, industry and power. 11, New York firehouses remained red-brick temples for New Yorkers groping for new understanding of a world they could never again take for granted.Īmong them was David Halberstam, the Pulitzer Prize-winning author known for dissecting the major movements and institutions of the 20th Century. And when it was over, the loss among firefighters was so staggering-343 dead, more than 600 children left behind-that they emerged as the undisputed symbol of a suffering city. Even as the towers burned, New Yorkers set out with gifts and anguish for a place that suddenly beckoned: the local firehouse.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)